Reciprocation : A Manipulative Social Process

Would you like buy this product for $40, or would you like to buy this new product on sale for $25 ....

Contents:

Introduction

Personalization Via Customization

Case Studies

Reciprocal Concessions

Rejection Then Retreat

Introduction

What is “Reciprocation”?

The rule says that we should try to repay, in kind, what another person has provided us. We are obligated (not by some external force but an internal urge) to the future repayment of favors, gifts, inIntroductionvitations, and the like. This rule is deeply implanted in us by the process of socialization that homo sapiens have undergone over thousands of years.

The rule says that we should try to repay what another person has provided us.

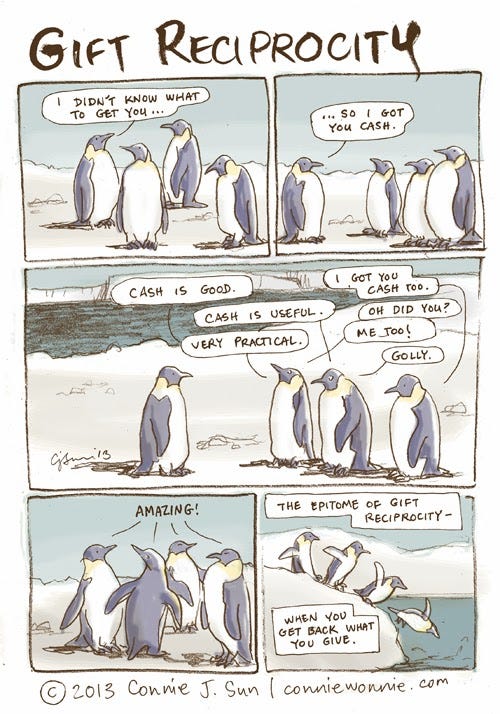

Reciprocated greeting cards, birthday gifts, and party invitations may seem like weak evidence of the rule's force.

Remember those free samples in the supermarket cookie shop? Or those welcome beverages offered to you and your wife in a jewelry store?

According to sociologists and anthropologists, one of the widespread and basic norms of human culture is embodied in the rule of reciprocation. The rule requires that one person try to repay, in form, what another person has provided. By obligating the recipient of an act to repay in the future, the rule allows one individual to give something to another with confidence that it is not being lost.

Another way the rule of reciprocation can increase compliance involves a simple variation on the basic theme: instead of providing a first favor that stimulates a return concession. One compliance procedure called the rejection then retreat technique, or door in the face technique, relies heavily on the pressure to reciprocate concessions.

How does the rule work?

Human societies derive a truly significant competitive advantage from the reciprocity rule and, consequently, they make sure their members are trained to comply with it. Each of us has been taught to live up to the rule from childhood, and each of us knows the social sanctions and derision applies to anyone who violates it. Because there is a general distaste for those who take and make no effort to give in return, we will often go to great lengths to avoid being considered a freeloader. It is to those lengths that we will often be taken and, in the process, be "taken" by individuals who stand to gain from our indebtedness.

As a marketing technique, the free sample has a long and effective history. In most instances, a small amount of the relevant product is given to potential customers to see if they like it. The beauty of the free sample, however, is that is also a gift and as such, can engage the reciprocity rule. A promoter who provides free samples can release the natural indenting force inherent in a gift, while innocently appearing to have only the intention to inform.

One of the supermarkets sold an astounding one thousand pounds of cheese in a few hours one day by putting out the cheese and inviting customers to cut slivers for themselves as free samples.

Personalization Via Customization

The rules enforce uninvited debts.

The Power of the reciprocity rule is such that by first doing us a favor, unknown, disliked, or unwelcome others can enhance the chance we will comply with one of their requests. However, there is another aspect of the rule, in addition to its power, that allows this phenomenon to occur. A person can trigger a feeling of indebtedness by doing us an uninvited favor.

The reciprocal relationship confers an extraordinary advantage upon cultures that foster them, and, consequently, there will be strong pressures to ensure the rule does serve its purpose. Little wonder that influential French anthropologist Marcel Mauss, in describing the social pressure surrounding the gift-giving process, says there is an obligation to give, an obligation to receive, and an obligation to repay.

The rule demands that one sort of action be reciprocated with a similar sort of action. A favor is to be met with another favor; it is not to be met with neglect and certainly not with attack; however, considerable flexibility is allowed. A small initial favor. Because, as we have already seen, the rule allows one person to choose the nature of indebting first favor ad the nature of the debt-canceling return favor, we cloud easily be manipulated into an unfair exchange by those who might wish to exploit the rule

Why it is that one small first favor often stimulates larger return favors?

One important reason concerns the clearly unpleasant characteristics of the feelings of indebtedness. Most of us find it highly disagreeable to be in a state of obligation.

It is not difficult to trace the source of this feeling. Because reciprocal arrangements are so vital in the human social system, we have been conditioned to feel uncomfortable when beholden. If

If we were to ignore the need to return another’s initial favor, we would stop one reciprocal sequence dead and make it less likely that our benefactor would do such favors in nature.

“There’s is nothing more expensive than that which comes for free.”

There is another reason as well. A person who violates the reciprocity rule by accepting without attempting to return the good acts of others is disliked by the social group.

One study found that servers who gave diners a piece of candy when presenting the bill increased their tips by 3.3 percent. If they provided two pieces of candy to each guest, the tip went up by 14 percent.

When seen in the light of this cost, it is not so puzzling that in the name of reciprocity, we often give back more than we have received.

Neither is it so odd that we often avoid asking for a needed favor if we will not be in a position to repay it. The psychological cost may simply outweigh the material loss.

When you visit a bar next time remember that even something as small as the price of a drink can produce a feeling of debt. If instead of paying for them herself, a woman allows a man to buy her drinks, she is immediately judged (by both men and women) as more sexually available to him.

Case Study:

Regan Study - Coca Cola

Psychologist - Denis Regan Conducted an experiment on reciprocation.

The experiment took place in a Museum, "art appreciation" rating arts. A subject who participated in the experiment had to rate the painting with a fellow subject name "Joe" who was the assistant of dr. regan.

The experiment took place under two conditions:

Joe did a small unsolicited favor for the true subject

Joe didn't do any favor for the true subject

Test 1:

After rating paintings for a while, joe left the room and came with 2 bottles of coke one for himself and one for the subject, saying "let's take a drink break, you also must be thirsty" or "I asked the experimented if I could get myself a coke, and he said OK so I bought one for you, too."

Test 2:

Joe returned from a two-minute break empty-handed.

Later on, when all the paintings were rated and the experimenter left the room, Joe asked the subject to do him a favor. He indicated that he is selling raffle tickets for a new car and if he sold the most tickets, he would win a prize.

Joe's request was for the subject to buy some raffle tickets at 25 cents a piece: "Any would help, the more the better."

The major finding of the study concerns the number of tickets subjects purchased from joe under two conditions.

Without question, Joe was more successful in selling his raffle tickets to the subjects who has received his earlier favor. Apparantly feeling that they owed him something, these subjects bought twice as many tickets as the subjects who had not been given the prior favor.

The result of the experiment: The Rule Is Overpowering

One of the reasons reciprocation can be used so effectively as a device for gaining another's compliance is its power. The rule possesses awesome strength, often producing a yes response to a request that, except for an existing feeling of indebtedness, would have surely been refused. Some evidence of how the rule's force can overpower the influence of other factors that normally determine compliance can be seen in the second result of the Regan Study.

Besides his interest in the impact of the reciprocity rule on compliance, Regan was also investigating how liking for a person affects the tendency to comply with that person's request.

To measure how liking towards joe affected the subject's decisions to buy his raffle tickets, Regan had them fill out several rating scales indicating how much they had liked Joe. He then compared their liking responses with the number of tickets they had purchased from Joe. He found that subjects bought more raffle tickets from Joe the more they liked him.

This alone is hardly a startling finding - people are more willing to do a favor for someone they like.

A more interesting finding was that the relationship between liking and compliance was completely wiped out in the condition under which subjects had been given a Coke by Joe

For those who owed him a favor, it made no difference whether they liked him or not; they felt a sense of obligation to repay him, and they did.

The subjects who indicated they disliked Joe, bought just as many of his tickets as did those who indicated they liked him.

The rule of reciprocation was so strong it simply overwhelmed the influence of a factor - liking for the requester - that normally affects the decision to comply.

Think of the implications. People we might ordinarily dislike unsavory or unwelcome sales operators'’ disagreeable acquaintance representatives of strange or unpopular organizations - can greatly increase the chance that will do what they wish merely by providing us with a small initiating favor.

Next time when you favor someone, say this :

"Listen, If our position were ever reversed, I know you'd do the same for me."

Instead "I would have done it for anybody", or "No big deal".

Examples :

In one study showed that mailing a $5 "gift" check along with an insurance survey was twice as effective as offering a $50 payment for sending back a completed survey.

Food servers have learned that simply giving customers a candy or mint along with their bills significantly increases tips.

In one study on McDonald's, it experimented that, the balloon was given after the children left the restaurant, and when the children of adult customers received a balloon as they enter the restaurant, the total family check rose by 25 percent. This included a 20 percent increase in the purchase of coffee - an item children are unlikely to order. Why? "A gift to my child is a gift to me"

In 2011, to celebrate its 40th anniversary Starbuck offered free online vouchers for a gift card. In an effort to heighten feelings of obligation associated with the gift, any customer accepting the voucher has to explicitly thank the company on social media.

The Not-So-Free Sample

AMWAY uses a concept called "BUG" a small bag or polythene full of AMWAY products for customers for 24,48 or 72 hours at no cost by an Amway salesperson. At the end of the day when customers use the BUG, it is 100% sales convert.

A promoter who provides free samples can release the natural indebting force inherent in a gift, while innocently appearing to have only the intention to inform.

Supermarkets, where customers are frequently given small amounts of a certain product to try. Many find it difficult to accept samples from the always smiling attendant, return only the toothpicks or cups, and walk away, instead, they buy some of the products even if they might not have liked them very much.

The reciprocity rule governs many situations of a purely interpersonal nature where neither money nor commercial exchange is at issue.

Reciprocal Concessions

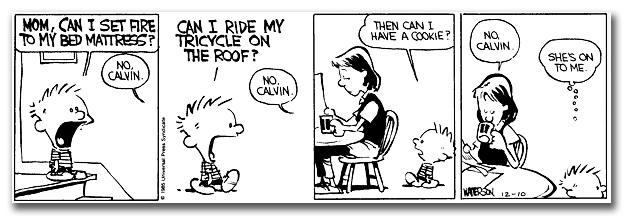

Robert Cialdini explains one of the scenarios of concessions - “I was walking along a street when approached by an eleven-or twelve-year-old boy. He introduced himself and said he was selling tickets to the annual Boy Scouts Circus to be held on the upcoming Saturday night. He asked if I wished to buy any tickets at $5 apiece. I declined. The boy said if you don’t want to buy any tickets, how about buying some of our chocolate bars for $1 each? I bought a couple of bars and realized that it was a reciprocal concession.”

An obligation to make a concession to someone who has made a concession to us.

Why should I feel obliged to reciprocate a concession?

The reciprocation rule brings about mutual concession in two ways. The first is obvious: it pressures the recipient of an already made concession to respond in kind. The second, while not so obvious, is pivotally important.

Because of a recipient’s obligation to reciprocate, people are freed to make the initial concession, and thereby, to begin the beneficial process of a concession, who would want to make the first sacrifice? To do so would be to risk giving up something and getting nothing back. However, with the rule in effect, we can feel safe making the first sacrifice to our partner, who is obliged to offer a return sacrifice.

Rejection Then Retreat

Because the rule of reciprocation governs the compromise process, it is possible to use an initial concession as part of a highly effective compliance technique. The technique is a simple one that we can call the rejection-then-retreat technique, although it is also known as the door-in-the-face technique. Suppose you want me to agree to a certain request. One way to increase the chances I will comply is first to make a larger request of me, one that I will most likely turn down. Then, after I have refused, you make the smaller request that you were really interested in all along. Provided that you structured your request skillfully, I should view your second request as a concession to me and should feel inclined to respond with a concession of my own - compliance with your second request.

Did the smaller request to which the requester retreated have to be small?

If our thinking about what caused the technique to be effective was correct, the second request did not have to be small, it only had to be smaller than the initial one.

Research conducted at Bar-Ilan University in Israel on the rejection then retreat technique shows that if the first set of demands is so extreme as to be seen as unreasonable, the tactic backfires. In such cases, the party who has made the extreme first request is not seen to be bargaining in good faith. Any subsequent retreat from that wholly unrealistic initial position is not viewed as a genuine concession and, thus, is not reciprocated. The truly gifted negotiator then is one whose initial position is exaggerated just enough to allow for a series of small reciprocal concessions and counteroffers that will yield a desirable final offer from the opponent.

There were three important findings that help us to understand why the rejection-then-retreat technique is so effective. First, compared to the two other approaches, the strategy of starting with an extreme demand and then retreating to the more moderate one produces the most money for the person using it. This result is not surprising in light of the previous evidence we have seen for the power of larger-then-smaller-request tactics to bring about profitable agreements.

How does one go about neutralizing the effect of a social rule such as the one for reciprocation?

It seems too widespread to escape and too strong to overcome once it is activated. Perhaps the answer is to prevent its activation. Perhaps we can avoid a confrontation with the rule by refusing to allow a requester to commission its force against us in the first place. Perhaps by rejecting a requester’s initial favor or concession, we can evade the problems.