Mental Models: The first principle thinking

Mental model series, this article is notes from what I have read, absorbed and synthesized about first principle thinking. (P.S - I write to learn, Not to teach).

Content:

Introduction: The first principle of thinking

Assumptions and using the first principle

Socrates Questioning

Conclusion

The First Principle

In layman’s terms, first principles thinking is basically the practice of actively questioning every assumption you think you ‘know’ about a given problem or scenario — and then creating new knowledge and solutions from scratch. Almost like a newborn baby.

On the flip side, reasoning by analogy is building knowledge and solving problems based on prior assumptions, beliefs, and widely held ‘best practices’ approved by a majority of people.

People who reason by analogy tend to make bad decisions, even if they’re smart.

STEP 1: Identify and define your current assumptions

“If I had an hour to solve a problem, I’d spend 55 minutes thinking about the problem and 5 minutes thinking about solutions.”

— Albert Einstein

Here are some examples from everyday life in business, health, and craft.

“Growing my business will cost a lot of money.”

“I have to struggle and starve to become a successful artist.”

“I just can’t find enough time to workout and reach my weight loss goals.”

When next you’re faced with a familiar problem or challenge, simply write down your current assumptions about them. (Note: You can stop here and write these down now)

STEP 2: Breakdown the problem into its fundamental principles.

“It is important to view knowledge as sort of semantic tree. Make sure you understand the fundamental principles, ie the trunk and big branches, before you get into the leaves/details or there is nothing for them to hang on to.”

- Elon MuskThese fundamental principles are basically the most basic truths or elements of anything.

The best way to uncover these truths is to ask powerful questions that uncover these ingenious gems.

Here’s a quick example from Elon Musk during an interview with Kevin Rose on how this works.

Somebody could say, “Battery packs are really expensive and that’s just the way they will always be… Historically, it has cost $600 per kilowatt hour. It’s not going to be much better than that in the future.”

With first principles, you say, “What are the material constituents of the batteries? What is the stock market value of the material constituents?” It’s got cobalt, nickel, aluminum, carbon, some polymers for separation and a seal can. Break that down on a material basis and say, “If we bought that on the London Metal Exchange what would each of those things cost?”

It’s like $80 per kilowatt hour. So clearly you just need to think of clever ways to take those materials and combine them into the shape of a battery cell and you can have batteries that are much, much cheaper than anyone realizes.”

This is classic first principles thinking in action.

Instead of following the socially accepted beliefs that battery packs were expensive, Musk challenges these beliefs by asking powerful questions that uncover the basic truths or elements i.e. carbon, nickel, and aluminum. Then, he creates ingenious innovative solutions literally from scratch.

STEP 3: Create new solutions from scratch

“The person who says he knows what he thinks but cannot express it usually does not know what he thinks.”

— Mortimer Adler

Once you’ve identified and broken down your problems or assumptions into their most basic truths, you can begin to create new insightful solutions from scratch.

Assumptions and using the first principle

Assumption: “Growing my business will cost too much money”

First principles thinking: What do you need to grow a profitable business? I need to sell products or services to more customers. Does it have to cost a lot of money to sell to new customers? Not necessarily, but I’ll probably need access to these new customers inexpensively. Who has this access and how you can create a win-win deal? I guess I could partner with other businesses that serve the same customer and split the profits 50:50. Interesting.

Assumption: “I just can’t find enough time to work out and achieve my weight loss goals.”

First principles thinking: What do you really need to reach your weight loss goal? I need to exercise more, preferably 5 days a week for an hour each time. Could you still lose weight by exercising less frequently, if so how? Possibly, I could try 15-minute workouts, 3 days a week. These could be quick high intense full-body workouts that will speed up my fat loss in less time.

Assumption: “I have to struggle and starve to become a successful artist”

First principles thinking: What do you really need to create great work and make a good living as an artist? I would need a reasonably sized audience to appreciate and buy my artwork. What do you need to reach a larger audience? I probably need to do some marketing, but I don’t like self-promoting so I’d rather not do this. Ok, is there any way for you to promote your work without being sleazy? Yes, if the focus of selling my artwork is meaningful with the purpose of serving the audience — then I could make more money to make more art, so I can serve more people.

Socrates Questioning

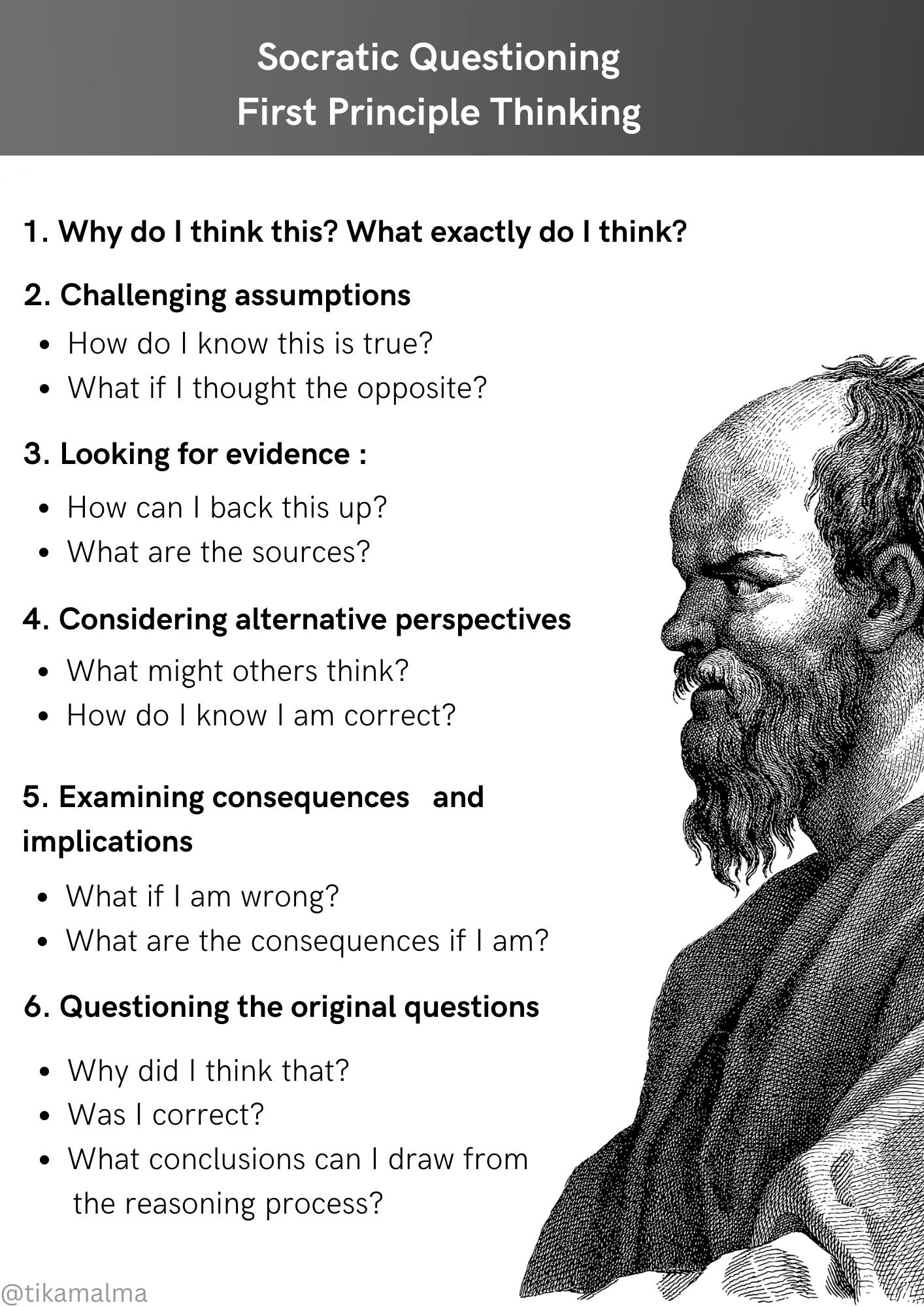

Socratic Questioning

Socratic questioning can be used to establish first principles through stringent analysis. This a disciplined questioning process, used to establish truths, reveal underlying assumptions, and separate knowledge from ignorance. The key distinction between Socratic questioning and normal discussions is that the former seeks to draw out first principles in a systematic manner. Socratic questioning generally follows this process:

Clarifying your thinking and explaining the origins of your ideas

Why do I think this? What exactly do I think?

Challenging assumptions

How do I know this is true?

What if I thought the opposite?

Looking for evidence :

How can I back this up?

What are the sources?

Considering alternative perspectives

What might others think?

How do I know I am correct?

Examining consequences and implications

What if I am wrong?

What are the consequences if I am?

Questioning the original questions

Why did I think that?

Was I correct?

What conclusions can I draw from the reasoning process?

Socratic questioning stops you from relying on your gut and limits strong emotional responses. This process helps you build something that lasts.

The Five Whys is a method rooted in the behavior of children. Children instinctively think in first principles. Just like us, they want to understand what’s happening in the world. To do so, they intuitively break through the fog with a game some parents have come to dread, but which is exceptionally useful for identifying first principles: repeatedly asking “why?”

The goal of the Five Whys is to land on a “what” or “how”. It is not about introspection, such as “Why do I feel like this?” Rather, it is about systematically delving further into a statement or concept so that you can separate reliable knowledge from assumption. If your “whys” result in a statement of falsifiable fact, you have hit the first principle. If they end up with a “because I said so” or ”it just is”, you know you have landed on an assumption that may be based on popular opinion, cultural myth, or dogma. These are not the first principles.

A first principle is a basic, foundational, self-evident proposition or assumption that cannot be deduced from any other proposition or assumption.

In mathematics and logic, a first principle is an axiom that cannot be deduced from any other within that system. An axiom is a statement that is taken to be true.

First-principles thinking is one of the best ways to reverse-engineer complicated problems and unleash creative possibilities. Sometimes called “reasoning from first principles,” the idea is to break down complicated problems into basic elements and then reassemble them from the ground up. It’s one of the best ways to learn to think for yourself, unlock your creative potential, and move from linear to non-linear results.

First Principle --- the difference between the cook and the chef. While these terms are often used interchangeably, there is an important nuance. The chef is a trailblazer, the person who invents recipes. He knows the raw ingredients and how to combine them. The cook, who reasons by analogy, uses a recipe. He creates something, perhaps with slight variations, that’s already been created.

The difference between reasoning by first principles and reasoning by analogy is like the difference between being a chef and being a cook. If the cook lost the recipe, he’d be screwed. The chef, on the other hand, understands the flavor profiles and combinations at such a fundamental level that he doesn’t even use a recipe. He has real knowledge as opposed to know-how.

What’s most interesting about Musk is not what he thinks but how he thinks:

I think people’s thinking process is too bound by convention or analogy to prior experiences. It’s rare that people try to think of something on a first principles basis. They’ll say, “We’ll do that because it’s always been done that way.” Or they’ll not do it because “Well, nobody’s ever done that, so it must not be good. But that’s just a ridiculous way to think. You have to build up the reasoning from the ground up—“from the first principles” is the phrase that’s used in physics. You look at the fundamentals and construct your reasoning from that, and then you see if you have a conclusion that works or doesn’t work, and it may or may not be different from what people have done in the past.

When we take what already exists and improve on it, we are in the shadow of others. It’s only when we step back, ask ourselves what’s possible, and cut through the flawed analogies that we see what is possible. Analogies are beneficial; they make complex problems easier to communicate and increase understanding. Using them, however, is not without a cost. They limit our beliefs about what’s possible and allow people to argue without exposing our (faulty) thinking. Analogies move us to see the problem in the same way that someone else sees the problem.

First-principles thinking clears the clutter of what we’ve told ourselves and allows us to rebuild from the ground up. Sure, it’s a lot of work, but that’s why so few people are willing to do it. It’s also why the rewards for filling the chasm between possible and incremental improvement tend to be non-linear.

Conclusion

“I don’t have a good memory.” People have far better memories than they think they do. Saying you don’t have a good memory is just a convenient excuse to let you forget. Taking the first-principles approach means asking how much information we can physically store in our minds. The answer is “a lot more than you think.” Now that we know it’s possible to put more into our brains, we can reframe the problem into finding the most optimal way to store information in our brains.

“All the good ideas are taken.” A common way that people limit what’s possible is to tell themselves that all the good ideas are taken. Yet, people have been saying this for hundreds of years, and companies keep starting and competing with different ideas, variations, and strategies.

Sometimes the early bird gets the worm and sometimes the first mouse gets killed. You have to break each situation down into its component parts and see what’s possible. That is the work of first-principles thinking.

“I can’t do that; it’s never been done before.” People like Elon Musk are constantly doing things that have never been done before. This type of thinking is analogous to looking back at history and buildings, say, floodwalls, based on the worst flood that has happened before. A better bet is to look at what could happen and plan for that.

“As to methods, there may be a million and then some, but principles are few. The man who grasps principles can successfully select his own methods. The man who tries methods, ignoring principles, is sure to have trouble.”

Reasoning from first principles allows us to step outside of history and conventional wisdom and see what is possible. When you really understand the principles at work, you can decide if the existing methods make sense. Often they don’t.

Many people mistakenly believe that creativity is something that only some of us are born with, and either we have it or we don’t. Fortunately, there seems to be ample evidence that this isn’t true. We’re all born rather creative, but during our formative years, it can be beaten out of us by busy parents and teachers. As adults, we rely on convention and what we’re told because that’s easier than breaking things down into first principles and thinking for yourself. Thinking through first principles is a way of taking off the blinders. Most things suddenly seem more possible.

References

Book - The Great Mental Models: General Thinking Concepts